ÇORSAM

ÇORSAM

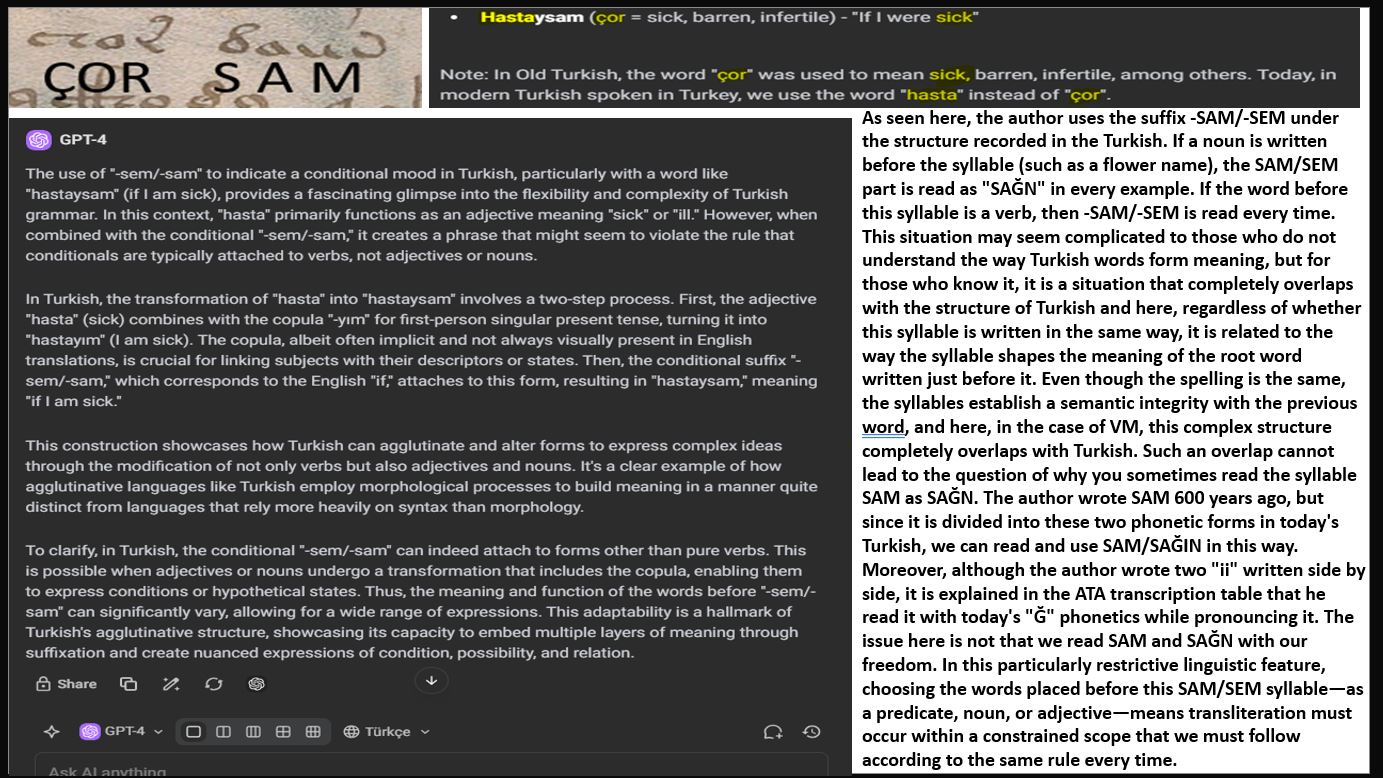

Original-Latin : ÇOR SAM

Transcript :

ÇORSAM > "if I were sick" (Eğer hastaysam.) As seen here, the author uses the suffix -SAM/-SEM under the structure recorded in Turkish. If a noun is written before the syllable (such as a flower name), the SAM/SEM part is read as "SAĞN" in every example. If the word before this syllable is a verb, then -SAM/-SEM is read every time. This situation may seem complicated to those who do not understand the way Turkish words form meaning, but for those who know it, it is a situation that completely overlaps with the structure of Turkish and here, regardless of whether this syllable is written in the same way, it is related to the way the syllable shapes the meaning of the root word written just before it. Even though the spelling is the same, the syllables establish a semantic integrity with the previous word, and here, in the case of VM, this complex structure completely overlaps with Turkish. Such an overlap cannot lead to the question of why you sometimes read the syllable SAM as SAĞN. The author wrote SAM 600 years ago, but since it is divided into these two phonetic forms in today's Turkish, we can read and use SAM/SAĞIN in this way. Moreover, although the author wrote two "ii" written side by side, it is explained in the ATA transcription table that he read it with today's "Ğ" phonetics while pronouncing it. The issue here is not that we read SAM and SAĞN with our freedom. In this particularly restrictive linguistic feature, choosing the words placed before this SAM/SEM syllable—as—a—predicate, noun, or adjective—means transliteration must occur within a constrained scope that we must follow according to the same rule every time.